e Franti rise.

Prima di parlare dei Franti, a mio parere un pezzo di storia della musica italiana, bisogna parlare di Franti. Sì, del personaggio [De Amicis, Cuore, 1886, Torino]. Il primo volantino della storia dei Franti, allegato alla prima edizione in cassetta di “Luna Nera” (1983), è una rielaborazione del testo di De Amicis.

Il libro “Cuore” rientra in un filone della letteratura italiana che qualche critico ha definito “edificante”. Nasce nell’Italia della seconda metà dell’800. Dunque, un paese unito nei palazzi della politica e della borghesia cittadina, non nelle case della gente. Servono meccanismi che possano creare quel senso di cultura condivisa e unità. Quello che negli anni ’50 fece la TV a fine ‘800 lo fece la scuola, diventata obbligo primario con la Legge Casati. Educare bambini alla responsabilità, al rispetto delle regole e ad uno stile di vita “gentile” affinché diventino gli italiani di domani. Intendiamoci, non è un complotto, ma De Amicis e Collodi, il papà di Pinocchio, rispondono “Presente!” a questo progetto culturale. Raccontano di bambini che vivono le loro peripezie, provano sulla loro pelle i prezzi degli errori e delle difficoltà (su tutti lo stesso Pinocchio e il Marco di “Dagli Appennini Alle Ande”), e diventano grandi.

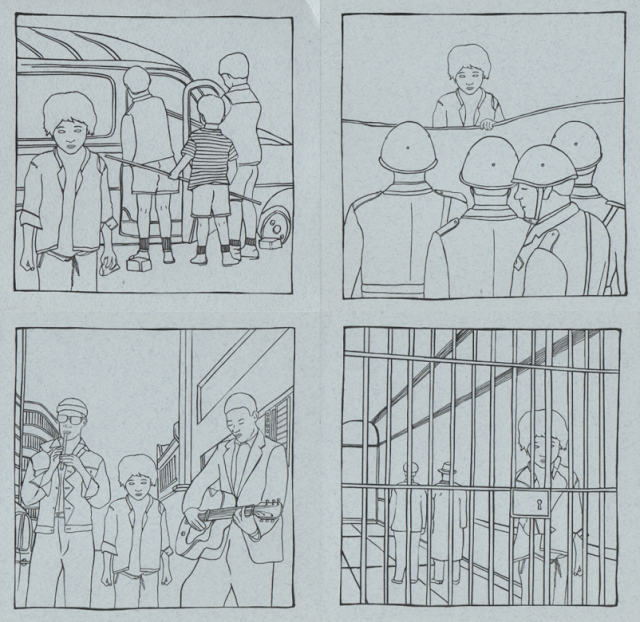

Eppure non c’è posto per tutti nel mondo di Cuore, per Franti non c’è posto. E’ restio alle regole, ai rapporti di forza, ha un ritratto quasi Lombrosiano (“Ci ha qualcosa che mette ribrezzo su quella fronte bassa, in quegli occhi torbidi”) e non lo si riesce a mettere in riga neanche con il senso di colpa (“Franti, tu uccidi tua madre!”). Per lungo tempo Franti è il ritratto del male, ancor più di Lucignolo perché quest’ultimo è semplicemente un bambino già perduto. Franti no, tutti cercano di metterlo sulla “buona strada” ma Franti si rifiuta con sprezzo e disprezzo. Poi Umberto Eco, in un celebre passo tratto dal “Diario Minimo”, ribalta questa prospettiva scrivendo “Elogio di Franti”. Esalta lo spirito ribelle, anti-conformista e refrattario alle regole borghesi che poi hanno aperto la strada al Fascismo. Eco lo dice chiaramente, s’immagina i compagni di scuola di Franti morti in trincea oppure nelle file dell’OVRA, la polizia segreta fascista. Esalta soprattutto il riso, visto come gesto di ribellione e rifiuto. “Chi ride è malvagio solo per chi crede in ciò di cui si ride”, solo se ci toccano nell’orgoglio e negli ideali.

La risata è la chiave per aprire la porta dei Franti, perché nel loro primo manifesto il testo deamicisiano è coperto e frammentato. Solo una parte è nitida, ben visibile e svetta sulle altre: “e Franti rise”. Forse non è un caso. La risata ribelle dei Franti nasce sui banchi di scuola, in una Torino che vive anni nei quali la città si sente sull’orlo del baratro. L’episodio che scuote la città è la morte di Carlo Casalegno, vice-direttore de “La Stampa”, ucciso dalle Brigate Rosse nel novembre 1977. In quello stesso periodo che va da quell’omicidio fino alla cosiddetta “Marcia dei 40mila” crescono un gruppo di ragazzi che fanno politica e musica. Il nome “Franti” diventa una scelta esistenziale, un manifesto culturale e politico in una città che ritrova, con gli anni ’80 e a distanza di un secolo esatto, la morale di “Cuore”. Franti vuole ribellione, rifiuto della gerarchia e della regola. Qual è la regola del sistema musicale italiano? E’ la SIAE, il diritto d’autore che loro bollano così: “Il diritto d’autore è una legge fascista che protegge la proprietà delle idee”. Non ne negano l’esistenza, semplicemente non gli riguarda. Stefano Giaccone lo ha ripetuto di recente, dicendo che è importante l’eco che hanno creato. Le storie collegate, il seguito di appassionati, l’ispirazione e l’esempio in altre band che seguono quel solco tracciato. Una strada che ognuno percorre a modo suo, passando da un furgone all’altro e da un progetto all’altro, ma con la mentalità di sempre. Franti possiamo essere tutti, quello che conta è l’adesione ad un’idea.

Ed è l’aspetto musicale che mi preme raccontare. In queste settimane abbiamo presentato “Il Lungo Addio”, CD che accompagna una ristampa di “Non Classificato”. Quest’ultimo nasce come doppio LP nel 1992 ed era la summa della produzione musicale dei Franti in quanto conteneva tutti i dischi usciti e qualche inedito. Fu curato dalla Blu Bus, forse il simbolo di quella concezione musicale. Era una casa di produzione nata dalla collaborazione tra i Franti e i Kina. Ospitò i loro dischi, progetti paralleli, e diverse altre esperienze (su tutte il meraviglioso, e consigliato, “Scimmie” dei Panico. Si trova ancora in qualche mercatino, lo so per esperienza diretta).

Le registrazioni de “Il Lungo Addio” risalgono al 1992 ma restano nascoste a lungo. Della “band originaria” ci sono Lalli, Vanni Picciuolo e Massimo D’Ambrosio, affiancati da Beppe Saroglia e Giancarlo Biolatti. Sono sei canzoni inedite e una cover di “Femme Fatale” dei Velvet Underground. Siamo in un momento in cui potrebbe sembrare anti-storico usare il nome Franti. Lalli e Stefano Giaccone avevano già composto qualcosa con i nomi Environs e Howth Castle, quest’ultimo affianca i Kina durante i concerti. Nelle logiche musicali “regolari” è un’altra storia. Invece tutto è Franti, anche con un altro nome perché è la mentalità che conta. Nelle canzoni si legge un filo conduttore, una tela di Arianna che ci aiuta ad uscire dal labirinto di nomi e diramazioni in un percorso ideale. Nel quale al centro c’è Lalli. Il primo è l’inizio di questo gomitolo: “Le Loro Voci”, tratta da “Luna Nera”. E’ la prima canzone scritta da Lalli. L’ispirazione le viene dal Massacro di Sabra e Shatila, eccidio all’interno dell’infinita scia di morte che colpisce il Libano. Immagini i bambini e le loro madri che cercano antidoti, vie di fuga ad un orrore nel quale tutto sembra uguale e allo stesso tempo lontano. Colpisce una frase che sembra fuori dal contesto bellico: “ti svegli e sei dentro un sogno / mi dici dormi, guardi l’ora / una piega cancella il tuo viso / suoni lievi la tua voce”. Eppure lì si consuma la tragedia perché chi si sveglia in un sogno vive tutti i giorni come un incubo. In “Ogni Giorno”, canzone da “Il Lungo Addio”, Lalli parla di giornate che passano per la natura ma non per certe persone. Dice “Io che non dormo per non perdere il tempo e libertà soffocate” per poi rendere visibile questo dramma, con la musica che lo evidenzia in maniera struggente: “Seduta le spalle al cielo / il giorno che nasce / seduti le spalle al muro / io che nasco e muoio un po’ ogni giorno”.

Nei Franti c’è spesso questo richiamo alle giornate che passano, alle abitudini che ci dilaniano ogni giorno (personalmente lo associo alla fabbrica, come elemento simbolico) e al vento come elemento liberatorio. Non a caso il primo solista si chiama “Tempo di Vento” ma il terzo punto di questo filo si trova nel secondo disco, “All’improvviso nella mia stanza”, nella canzone “Testa Storta”. Prima del finale, molto bello e malinconico, Lalli dice “La testa storta / la sete che brucia / le spalle confuse / in terra più grande / la mano che sembra ballare / tra vigne e lavanda / nel bosco che dal finestrino / a guardarlo è tutt’uno col mare”. Ci descrive un viaggio, l’attesa e la sua essenza, fatta d’incertezze (la testa storta del titolo). Alla base non c’è la paura ma la ricerca di qualcos’altro. Di liberatorio e consolatorio allo stesso tempo. La genesi di questo brano è quasi emblematica, contiene la simbologia di questa ricerca. E’ scritta da Lalli e Pietro Salizzoni, un binomio felice nato in un momento di crisi della cantante astigiana. Lo ha raccontato in una recente intervista. Purtroppo ha lasciato meno tracce di quanto uno da fuori possa sperare ma ciò che conta è altro: è l’intensità, l’eco che ci lascia. La lezione dei Franti.

Questa è una chiave di lettura, una mia visione. Non so dire se sia quella corretta. Penso che quando riesco ad essere autentico, a rifiutare certe logiche e fare attenzione al vento che passa cercando di raccoglierlo senza farmi trascinare un po’ Franti lo sono anch’io. Lo possiamo essere tutti.

Nell’ambito di questo post, linkiamo contestualmente un documento interessanti dal nostro canale YouTube. Non abbiamo avuto il consenso diretto dell’etichetta stella*nera per l’upload, ma in fede del principio di circolazione senza fini di lucro abbiamo deciso di condividere i contenuti del cd Estamos En Todas Partes, regolarmente acquistato. Riportando le parole presenti nell’inlay del CD stesso: “no copyright / il diritto d’autore è una legge fascista che protegge le proprietà delle idee. la riproduzione di questo materiale è libera a patto di rispettarne integralmente i contenuti e di mantenerne la circolazione all’esterno di qualsiasi logica di profitto. questo cd non è destinato alla diffusione commerciale nei negozi: il ricavato della sua diffusione va ad alimentare i fondi neri di a/rivista anarchica [[email protected], www.arivista.org]”

ENGLISH VERSION

and Franti laughed.

Before starting to talk about the band Franti – according to me an important fragment of Italian’s music history – we should talk about Franti himself, the character. The first flyer made by the group was attached to their first tape release called “Luna Nera” (1983) and it contained a rework of a script by Edmondo De Amicis. “Cuore” is a book that was written in the second half of the XIX century, and some critics had defined inspiring (you can read it here). The Italy of the period was a nation kept united not by common people, yet from politics and middle/high classes interests. There was a need of cultural binding, just like the TV provided in 50’s. That role was taken by school, which turned to compulsory education with Legge Casati: its goal was to educate children to responsibility, following the rules and living politely, growing the perfect Italians to be. De Amicis and Carlo Collodi (Pinocchio’s writer) joined firmly this cultural project. They wrote about children living their adventures and paying the consequences of their own mistakes (just as Pinocchio and Marco too from “Dagli Appennini Alle Ande“).

But there’s no place for Franti in the world described in Cuore. He is against rules and power relationships. His face may fit a Lombroso-ian description (“There is something beneath that low forehead, in those turbid eyes”), and not even guilt could make him regret his doings (“Franti, you are killing your mother!”). Franti was seen as a portrait of evil for many years, even worse than Candlewick because he already was a lost child. Franti is not lost yet: everyone pushes him to find his path but he refuses with contempt. In a famous passage taken from “Diario Minimo”, called “Elogio di Franti” (“In Praise Of Franti”), Umberto Eco reversed the most popular point of view about the character. Eco enlights his rebellious spirit and his will to not conform to bourgeoisie’s rules, the ones that would have opened a path for Italian Fascism. Eco widly imagined all Franti’s schoolmates dead in a trench, or joining the OVRA (the secret fascist police). Above all, he celebrates Franti’s laugh, seen as THE sign of rebellion and refusal (“[Who laughs appears to be evil only to whom who believes in what the laugh’s on”]). Laughter is the keypoint that helps us understand the band’s manifesto, since in their tape De Amicis’ words are covered and fragmented. We can only immediately see the phrase: “and Franti laughed”. I guess it is no coincidence at all.

The band’s rebel laugh was born early inside a classroom in the city of Turin, that was facing a difficult period at the time. The town was shocked by the assassination of Carlo Casalegno, the co-head of ‘La Stampa’ newspaper, who was killed by Brigate Rosse in November 1977. A bunch of guys who were into music and politics began to rise in the period between the killing and a huge march of 40000 workers (Marcia dei Quarantamila). The name “Franti” became a flag for an existential choice, a cultural and political manifesto in a city that re-discovered “Cuore”‘s morality only a century after the book was published. Franti wanted rebellion and refusal for hierarchy and rules. The ruler of Italian’s musical system is SIAE and its copyright, which is portraited by them as “a fascist law, protecting propriety of ideas”. They did not want to deny its existence; they just weren’t concerned with. Stefano Giaccone recently re-confermed this, and he also stated that the only thing that mattered was the echo that followed the band. The important stuff were the relationships they created, the people following them, and being seen as inspiration from other bands. A road that everyone walks in a unique way, from a van to another, from a project to another, with a never changing state of mind. We can all be Franti, all that matters is just to embrace an ideal.

However, the musical side of the Franti story is what we mostly care to tell. In July we presented “Il Lungo Addio”. The CD was included in a re-press of “Non Classificato”. The latter came out in 1992 as double LP and it was the summae of the whole production of the group, plus unpublished tracks. It was edited by Blu Bus, a label grown out from a collaboration between Franti and Kina. Blu Bus published their albums, other bands’ works (above all the awesome “Scimmie” by Panico) and side projects. “Il Lungo Addio” was recorded in 1992 but it remained unpublished for a long time. Here we have only Lalli, Vanni Picciuolo and Massimo D’Ambrosio from the original band, together with Beppe Saroglia and Giancarlo Biolatti. The tracklist contained six unreleased tracks and a cover of Velvet Underground’s “Femme Fatale”. In that period someone would say that using the name ‘Franti’ could sound totally anachronistic. So, Lalli and Stefano Giaccone started to produce new tracks calling themselves Environs and Howth Castle, often playing with Kina. The same, they sounded like Franti, even using other names. The state of mind is what really matters.

In their songs there’s always a recurring element, such as an Ariadne’s thread, allowing us to leave safely a labyrinth made of words in which center there’s Lalli. The first piece of this ball of yarn is “Le Loro Voci”, from “Luna Nera”. It’s the first song written by Lalli. She was inspired by Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon. Here there are pictures of mothers searching for antidotes together with their children, stories of escaping from that boundless horror that seems strangely distant. There’s a phrase in particular which seems to be not related to war: “you wake up in a dream / you tell me to sleep, look at the time / a line erase your face / your voice is so light”. This is the real tragedy indeed: those who awake in a dream are condamned to live out a nightmare. In “Ogni Giorno” (out of “Il lungo Addio”) Lalli talks about the end of the days, for nature as a whole and not for all the people. She sais: “I don’t sleep not to lose time, and the suffocated freedom”, and then this cruel trouble is clearly showed off, the music stressing her struggle; “I sat down, my back to the sky / the day is coming up / everybody sit down, the backs to the wall / I am born and dead every day”. Days gone by and exhausting life routines are often recalled by Franti (to me these are well represented by the image of the factory). The wind is the main metaphor of freedom, as the title of her first solo work says (Tempo di Vento). I want to mention also the song called “Testa Storta” out of her second album “All’Improvviso Nella Mia Stanza“: just before the closure of the song Lalli says “The tilted head / burning by thirst / confused shoulders / in a bigger land / the hand seems to dance / among the vineyards and lavender / inside the woods that seems to be a whole with the sea when you look by the carwindow”. She tells us about a journey made of waiting and of uncertainty. At the foundation there’s the will to search for something new, and no place for fear. Something capable to free and comfort at the same time. The track represents the perfect example of the state of searching itself. It was written by Lalli and Pietro Salizzoni, who decided to compose together – with great results we must say – in a particular moment of outbreak of Lalli’s life, as she mentioned in a recent interview. The pair did not leave us as much productions as one’s would have hoped for. However, it’s the intensity of the songs – and their echo in time – that matters. That’s the band Franti’s lesson indeed.

This is just an interpretation, just a personal point of view. I can’t say if it’s the right one. I think that when I’m true and when I’m able to refuse some rationality, reaching for the wind without being dragged away, I feel I am Franti. All of us could be him.

To end the article, we present here a very interesting document out of our YouTube channel. We didn’t get the permission by the label stella*nera to upload them, Yet, following the principle of sharing without any kind of money drawback, we decided to put online the Estamos En Todas Partes CD contents. The CD was regularly bought. Reporting the words written in the inlay of the compact discs itself: “no copyright / the copyright is a fascist law protecting the ownership of ideas. the reproduction of this material is completely free as well as the contents are reported integrally and spread outside any will to take profit out of it. this cd was not meant to be sold in shops: the proceeds are destined to the black founds of a/rivista anarchica [[email protected], www.arivista.org]”

Are you enjoying what you see on PAYNOMINDTOUS? If that’s the case, we’d like to kindly ask you to subscribe to our newsletter, our Facebook group, and also to consider donating a few cents to our cause. Your help would be of great relevance to us, thank you so much for your time!

PAYNOMINDTOUS is a non-profit organization registered in December 2018, operating since late 2015 as a webzine and media website. In early 2017, we started our own event series in Turin, IT focused on arts, experimental, and dancefloor-oriented music. We reject every clumsy invocation to “the Future” meant as the signifier for capitalistic “progress” and “innovation”, fully embracing the Present instead; we renounce any reckless and ultimately arbitrary division between “high” and “low”, respectable and not respectable, “mind” and “body”; we support and invite musicians, artists, and performers having diverse backgrounds and expressing themselves via variegated artistic practices.